Welcome to My New Philosophy Blog

There are those people who write novels in this world to become famous and make money, bestseller-list types who stalk the market and trend like wolves, noses twitching for the next fix of relevance, casting their prose as bait for film options. Their faces, you see, float on the backs of dust jackets in big-box bookstores, grinning through a veneer of mass-appeal, all flashbulb and advance checks. Some of them probably never even cared if the words themselves meant anything, so long as the words accumulated, like landfill, under their name. Even when the author photo is blurred or cropped, the impulse beams through: they want to be known, to be quoted at dinner parties, to have their words dropped like incantations by late-night hosts and columnists. They chase the reader’s gaze as if it might transmute them into something more than a clever monkey in a blazer with a contract. If you ever talk to one at a conference—say, over the ruinous chardonnay of a hotel bar—listen for their hunger: it is half shark, half showman. They speak of “platform,” not legacy; of “audience,” not language. Their epics become franchises, their epistolary novels thinly-disguised bid sheets. Fame, money, or at least a memorial plaque on the wall of a chain coffee shop in a suburb.

There are those people who write novels in the world because they’re notorious, or who seem to take a weird, unwholesome pleasure in the propagation of violence and mayhem. They’re not the same as the bestseller wolves, exactly—instead of hunting the herd, they want to scatter it, incite a stampede, let the bodies pile up and call it literature. They sharpen their sentences on the bones of other people’s suffering; they build entire careers out of spilling blood on the page, delighting in the fallout and public outrage. They are the connoisseurs of infamy, the engineers of controversy—writing not so much to seduce the reader as to punch them in the face, leave a bruise, maybe even a permanent scar. Their works become the forbidden objects in high school lockers and under dorm-room mattresses, banned from libraries but circulating like a viral disease in the dark. you know them by the way they cultivate enemies, by the way their very names can silence a room, by the way they seem to relish the public burnings and the hate mail. They want to be infamous, and if it takes a little literary arson to get there—burning bridges, torching reputations, immolating the last remaining taboos of the century—they’ll light the match, every time. There is a theory that these writers are acting out a larger social necrosis, the death wish of an empire in its decline, but I think it’s something simpler and sadder. They like to make trouble, and this is the only way left that’s legal.

Then there’s the third way. The third way is made up of people who never had any right to write a novel at all, at least according to the world. Not the trust fund Ivy kids or the wounded prodigies, but the ones who came to language late, sometimes backwards, sometimes sideways, sometimes as a byproduct of jobs, or illness, or the accidental slant of immigrant voices at the dinner table. They were born into the permanent backdraft of the American machine, churning out their years in check-out aisles, food courts, car washes, nursing homes, and high school kitchens—learning the shape of words only as a function of survival, not as a ladder to some cathedral of taste. These writers didn’t start with books in the house, or if there were books, they came second-hand, water-damaged, or found in a dumpster beside the old TV and the remnants of last night’s Hamburg and Peas. They wrote because no one else was ever going to write about them, or for them. They wrote because the stories in their heads were the only inheritance they’d ever be allowed to keep.

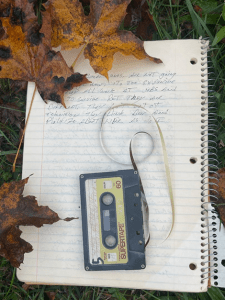

You’d know them, if you met one, by the stains on their hands or the way their knuckles tell the history of shit jobs and self-repair. Their sentences might have strange gaps, like teeth knocked out in a bar fight, and their grammar might lurch or limp, but every line is a compulsion, a work-around for the way the world never gave them a straight shot. Some of their stories are patched together from borrowed library time, written in spiral notebooks that crook and …., or typed in the flicker between the second and third shift at a job that’s killing them. Many writers exist in a hidden canon, unpublished and uninterested in publishing, doubting anyone would care. Who would listen? The answer: almost no one, until the day someone does, and then it gets out that the best stories come from the people with the least reason to tell them. If you read these stories, you’d find yourself in the company of voices that have never been on a panel or a syllabus, voices that have gone hoarse from shouting over the TV or the factory floor, voices that know what it’s like to get a rejection letter and use it to line a birdcage, or light a fire, because that’s what rejection is good for—fuel or bedding.

They are not much for manifestos or trends, these working class scribblers. If you asked what they wanted, they might say something like: “I just want to tell it like it was.” Or maybe: “I want to make a story that sounds like how people really talk, not how they think they should talk on the radio.” They live in places where literature is mostly a rumor, and “writer” is maybe the word for the guy who sets up the menu boards at the pizza place. Their ambitions are not for accolades, but for accuracy: to get the feeling right, the moment right, the punchline right, the way the world can be cruel and hilarious in the same breath. Their audience might be no one at all, or maybe just the one person they secretly love, or hate, or need to impress because that person is their entire universe and the only review that matters. They don’t have MFA workshops, but if you listen, the break room or the bus stop or the back of a Denny’s at three a.m. is its own kind of creative writing seminar, and you can hear the edits happening in real time.

Now and then, one of these writers gets loose in the world and the world doesn’t know what to do except make it a novelty, an anomaly, a “voice from the margins.” They get described in profiles with words like “gritty” or “authentic” or “raw,” as if the work itself is a slab of meat and not the fragile labor of a person who would have gladly taken a better life over the chance to write about a miserable one. But here’s the trick: their stories will outlive all the others, because they contain something the market can’t synthesize, and the controversy-mongers can’t fake—something like truth, or pain, or a sense of humor about the whole goddamn mess. It’s the third way, the unglamorous path, the slow leak of language from the bottom of the world. This story is written by one such person.

E Micheal Bablin

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.